The latest federal data from the National Center for Education Statistics shows that schools have made student mental health a critical focus, with almost 90% increasing social and emotional support during the 2021-22 school year. This trend highlights an increasing recognition that mental health is vital to academic success and well-being. Yet despite the progress made in this area, significant hurdles remain.

According to a survey by the National Center for Education Statistics (representative of about two-thousand seven-hundred public schools in the United States), the two most noticed barriers to having a capable mental health program are a lack of funding and a shortage of licensed mental health professionals. 39% of mental health professionals view these as the main reasons why the schools are not able to provide all the necessary help to their students.

Less complicating is the national shortage of school psychologists and other in-school mental health providers. Kelly Vaillancourt Strobach, director of policy for the National Association of School Psychologists, said one psychologist for every five hundred students is ideal. But most districts cannot meet that mark. Some schools report having one psychologist for as many as two thousand students. That leaves the psychologists on the job with heavy caseloads and makes it tough to provide individualized care that is much needed by many students.

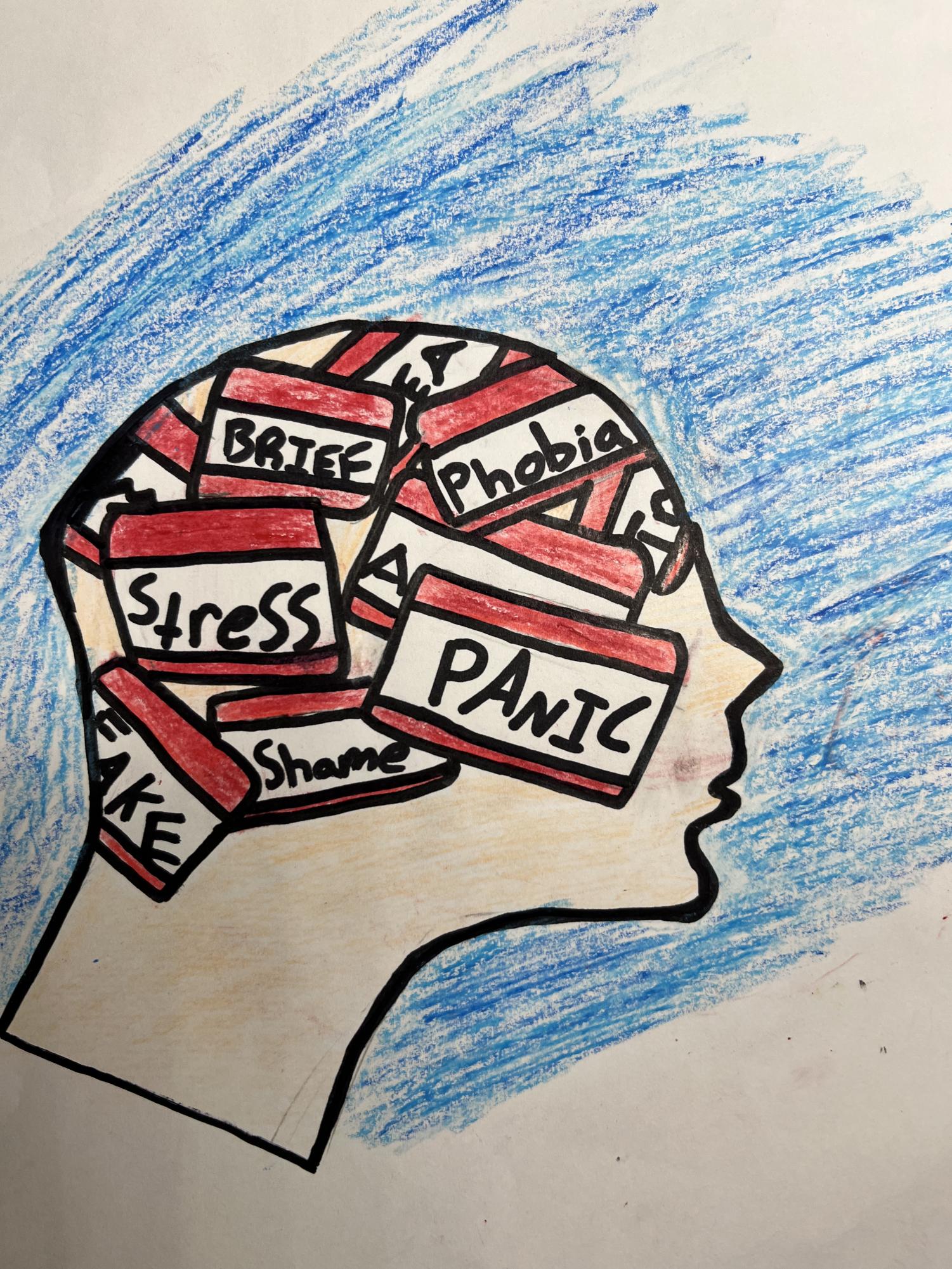

Brandon Flamenco Romero ‘27 states, “Taking care of my mind is just as important as taking care of my body—both deserve kindness and rest.”

While the federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund money has temporarily boosted many mental health services, many districts are worried about their sustainability when funding runs out.

Another major issue remains: the disproportionate burden carried by teachers themselves. However, Amir Gilmore, associate dean of equity and inclusion in the College of Education at Washington State University, called the expectation that teachers could take on mental health responsibilities and their teaching jobs unrealistic and unsustainable.

Ian Escobar-Castro ‘28 states, “Mental health isn’t a weakness; it’s just part of being human. I’m allowed to have bad days and still be strong.”

While Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) programs are becoming ubiquitous, they are no substitute for the specialized care provided by licensed counselors. This would increase the workload for teachers, leading to burnout and diminishing their core role of educating students.

This lack of mental health resources is just one symptom of a broader inequity in education. Richer districts can afford to hire staff and maintain programs; poorer ones often need help too. These inequalities are further exacerbated by political resistance in some communities where taxpayers seem unwilling to vote for budget increases to finance schools. According to Amir Gilmore, this is an issue tangled way deep in systemic inequities of race, class, and access.

“This is an issue of race and class and access, and that’s what education right now is very inequitable,” Gilmore says.

According to Adithya Abish ‘28, “Mental health positivity has to be reinstated more in teenagers’ lives. I can guarantee every kid has gone through ups and lows in life, and more positivity around schools, neighborhoods, and communities can help kids cope with their mental health struggles.”

Adithya said the ambitious goal requires a commitment throughout the community so that the necessary mental health support can reach all students, regardless of their background. Abish also said the challenges to providing adequate mental health resources are comprehensive, ranging from funding issues to workforce shortages to systemic inequity.

These all require a multi-faceted approach: sustained funding, recruitment and retention of mental health professionals, and importantly, a collective effort at reducing disparities. By placing student mental health front and center, schools have the potential to create environments where all students will have an opportunity to grow, both academically and emotionally. Otherwise, the most vulnerable of them are certain to fall by the wayside of the education system.