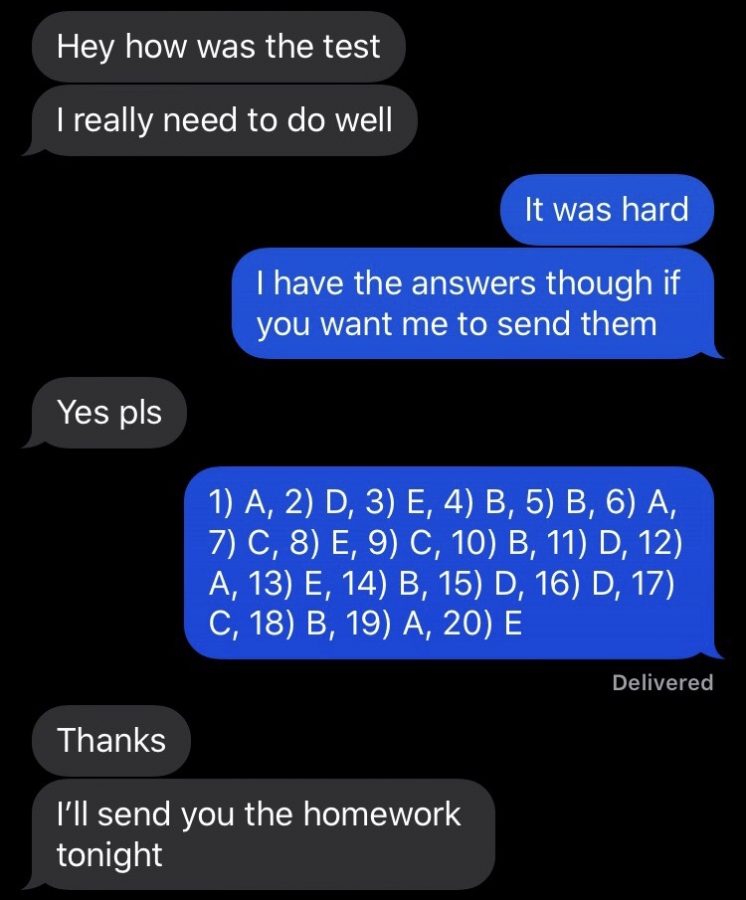

80% of BHS students report that they have either cheated or witnessed a peer cheating. 97% of teachers report that they have witnessed students cheating. Evidently, we are experiencing a high volume of cases of academic misconduct. But how many of these cases go unreported and without punishment? The vast majority. Exploring the perspectives of both students and teachers on the issue shows that we are facing a misalignment of the definition of cheating and variation in opinion on effective means of prevention.

One of the primary issues with academic misconduct is that many students view ‘shortcuts’ on assignments as a necessity. They see copying homework, asking peers about details of assessments, or even having other students complete assignments for them as a more efficient method of maintaining their grades.

Charlotte Lewis ‘20 said, “While I do not condone cheating, especially on quizzes and tests, I believe that the overwhelming emphasis on the importance of one’s grades for their future prospects encourages students to cheat…With grades holding the significance that they do, can you blame students for wanting to do everything in their power to get good grades?”

There has been a clear upward trend in cheating rates in recent years across the country. A national survey by The Josephson Institute Center for Youth Ethics polled nearly 50,000 high school students and found that one in three students admitted to using the Internet to plagiarize an assignment.

As reported in The New York Times, Howard Gardner, a cognitive psychologist and professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, is unsurprised at the rising levels of cheating on a national scale. He told The Times that over the 20 years he has studied academic integrity, he found that “the ethical muscles have atrophied,” largely because of a social reverence of success, regardless of how it’s achieved.

In a schoolwide survey, students and teachers were asked about whether or not they classified different behaviors as cheating. From that survey, only 37.7% of students believe copying homework is cheating. 100% of teachers believe the same. Copying homework is defined as a form of cheating in the BHS Student Handbook. With such a clear incongruity in how the members of our school community classify cheating, it’s foreseeable that infractions are so frequent. Students and teachers are not seeing the perspective of the other party.

Ms. Cerza said, “Cheating is a conscious decision and a reflection of morals and character. There’s a purpose in all of the assignments that I give, so to resort to a dishonest behavior is disappointing. I put so much care into the time and space of the four walls of my classroom. I invest myself – there’s a part of me in this job, they are inextricably linked.”

This sentiment hints at a broader idea. Cheating, from the moment a student has the idea to cheat to their eventual punishment–or lack thereof–is a dehumanized process. There’s a lack of connection between the action and the consequence because in most reported cases of cheating, the student will likely get a zero on the assignment and a few points added to their record, but they will not have a conversation with their teacher about their actions.

Currently, the policy regarding academic misconduct states that the first offense will result in “5-20 points, a zero on the assignment, teacher contact with a parent, and/or other disciplinary action.” The only formalized difference for any subsequent offenses is that the points added to a student’s transcripts changes to 10-20. The most interesting part of the policy is the use of “and/or other disciplinary action.” It’s reasonable to say that the severity of infractions should affect the punishment, but with 80% of the school population admitting to cheating or witnessing cheating, it’s clear that the current policy is ineffective in curbing academic misconduct.

There has been a clear shift in this policy throughout the years. It has become more open to interpretation. A prime example is the declaration of academic integrity that all students must sign before taking a final exam. Before 2014, the language in the declaration stated that violations of academic integrity “will” result in disciplinary action, and then specifically outlined what disciplinary action would ensue. After 2014, the language stated that violations of academic integrity “may” result in disciplinary action, and is nonspecific regarding what that disciplinary action would include.

Ms. Cerza, who teaches psychology and is an expert in industrial-organizational psychology, believes that a shift in policy is in order. In her own experience, having a professional conversation with a student who was cheating offers a chance for reflection and a space to learn and grow. She believes that the most effective consequence for violations of academic integrity would be to have one-on-one conversations, student to teacher, to create a level of understanding and connection.

“We have to have more of these conversations, now more than ever. We’re here to help children learn about themselves and we’re here to do more than teach our curriculum. We need to give students the opportunity to reflect on their choices,” she said.

Discipline can be a learning opportunity. It’s important to make mistakes and grow from them, especially before entering the collegiate or professional realms, where consequences could be much more damaging. Cheating will likely never be completely eradicated, but if students, teachers, and educational institutions as a whole work to understand the complexity of the motivations and repercussions of cheating, the frequency and severity of offenses would likely decrease.

Good Article • Mar 20, 2020 at 5:27 pm

Good article, but I want to hear more about why so many students feel motivated to cheat