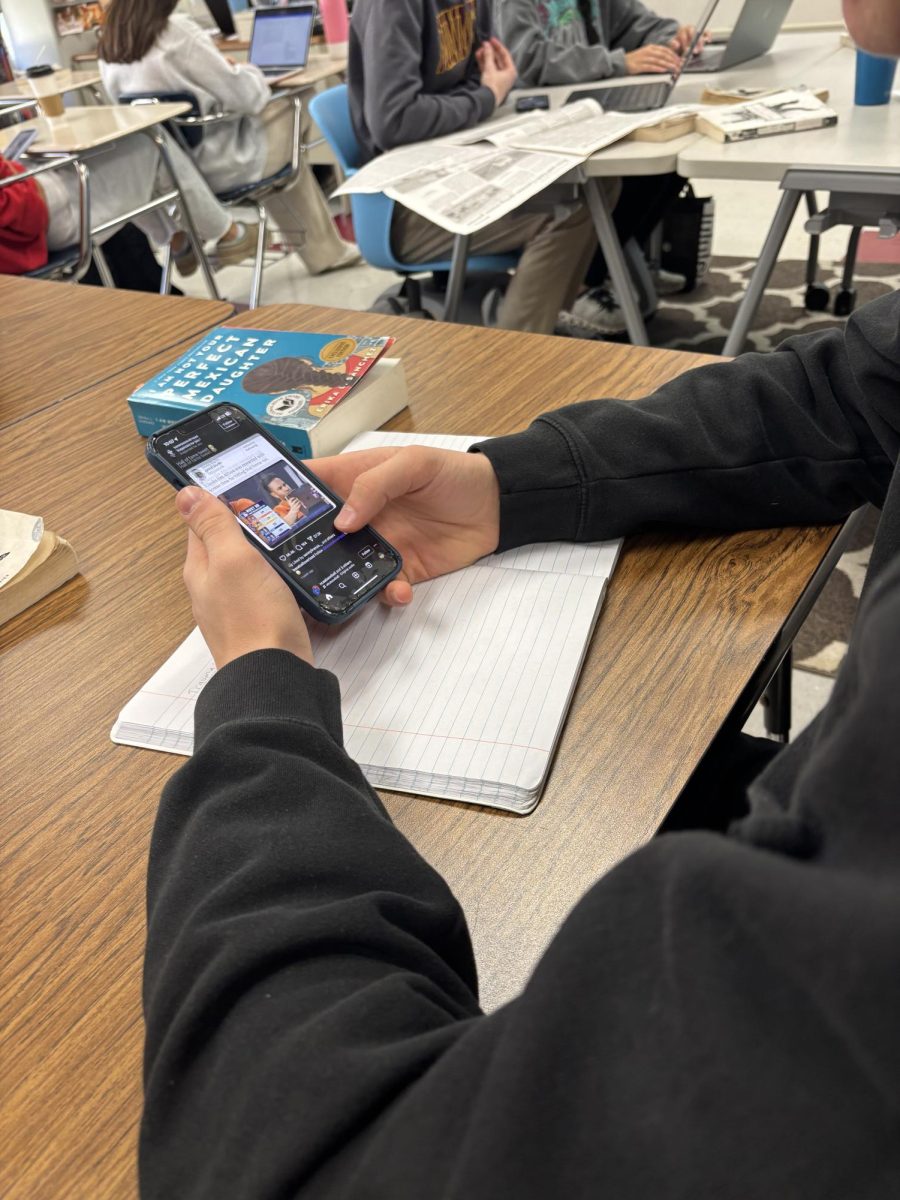

Following the pandemic and a general societal return to hobbies long neglected, an interesting phenomenon has emerged in which reading has once again come to the forefront of the public’s attention. More specifically, amongst teenagers- a group that has long been notorious for their pious devotion to technology and rejection of traditional media consumption such as reading. In spite of this, the hashtag “Booktok” on the popular app Tiktok has acquired an astounding 78.9 billion views, a tag in which influencers promote their favorite novels and authors.

So, is this uptick in the consumption of literature invariably beneficial to today’s youth? Or is this simply a pseudo-intellectual trend that will pass as quickly as it rose to prominence? To understand the legitimacy of these claims, it’s important to examine the stories that are popularly consumed. Additionally, we must remain skeptical of the quality of such novels and how their prevalence is shaping a generation’s understanding of literature.

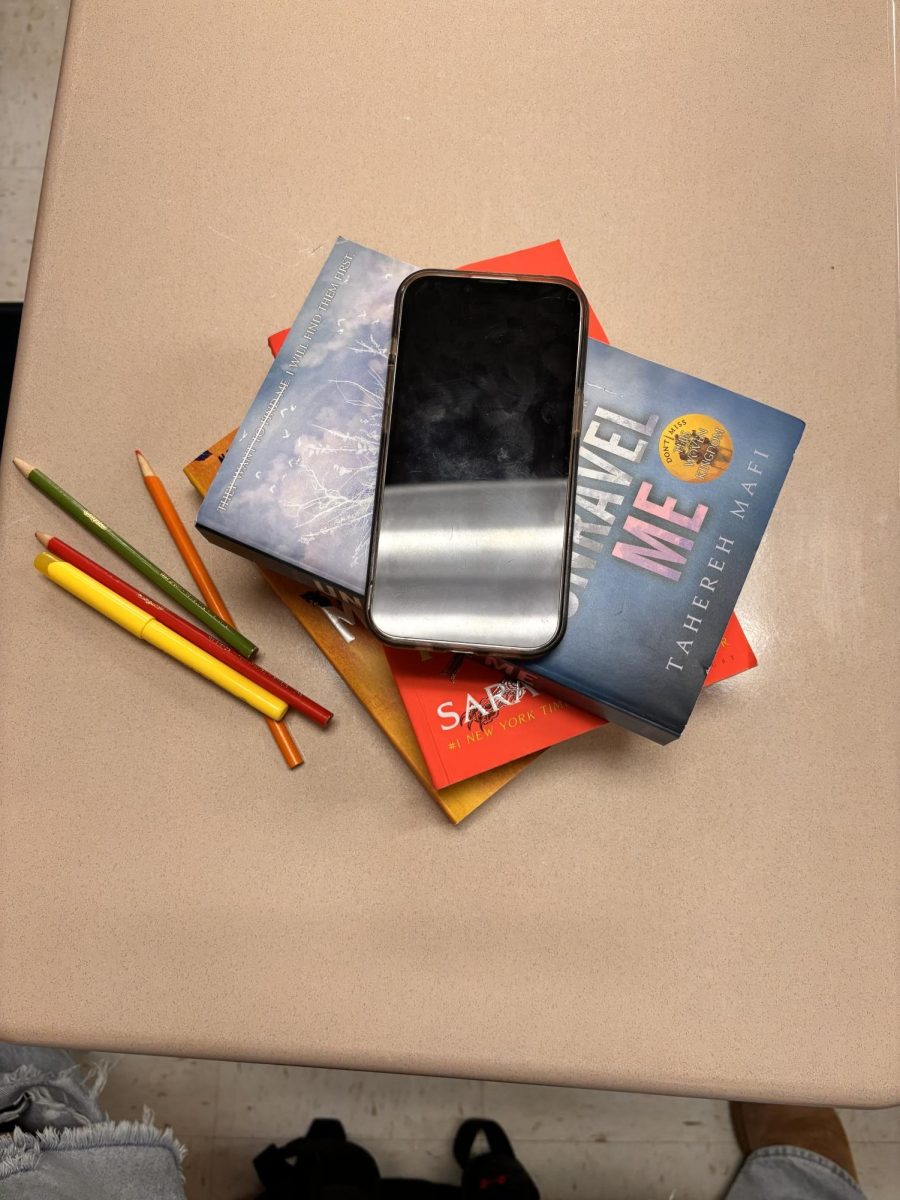

Colleen Hoover, Penelope Douglas, Sarah J. Mass, Holly Black, and Emily Henry are just some of the names most associated with “booktok” and its most popular novels, but are these figureheads the best representatives for new readers who are delving into the world of literature for the first time?

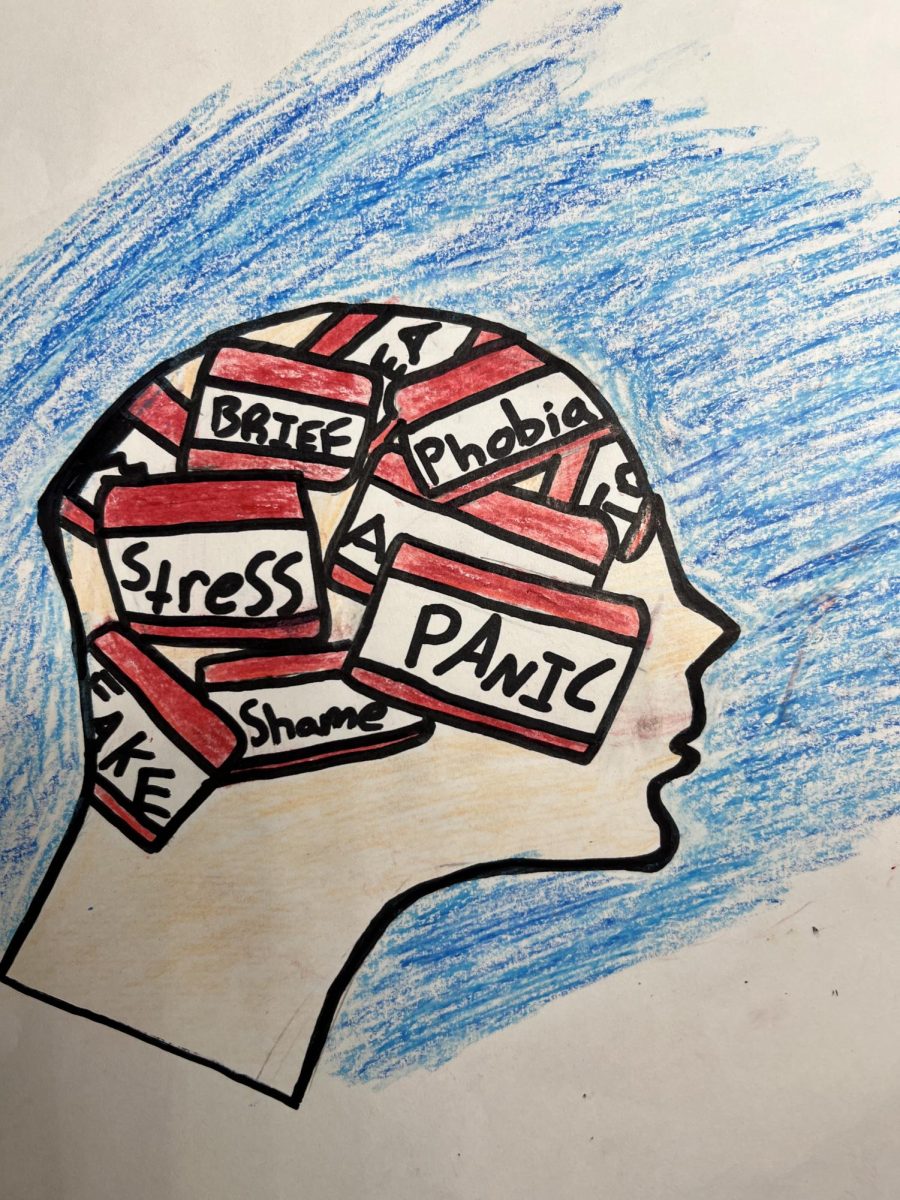

While it is impossible (and arguably pretentious) to assume new readers should immediately gorge themselves on classic novels and “intellectual” reads, it is worth noting that the cyclical nature of trendy books is indeed problematic in a sense. Authors such as Hoover and Douglas have come under criticism in recent years for their handling of serious topics such as domestic abuse, or mental illness and their supposed “romanticization” of the issue.

However, I am not interested in exploring the legitimacy of these claims surrounding the novels themselves, rather highlighting how such stories that are often criticized for their surface level takes on such complex issues can have negative implications for young readers.

These stories are simply not challenging young readers, but it is understandable that this is part of the appeal. There is nothing inherently wrong with the consumption of a frivolous read, in fact the argument there is lacks nuance as it falls into the trap of denouncing the interests of teenage girls for no other reasons than those rooted in misogynist rhetoric.

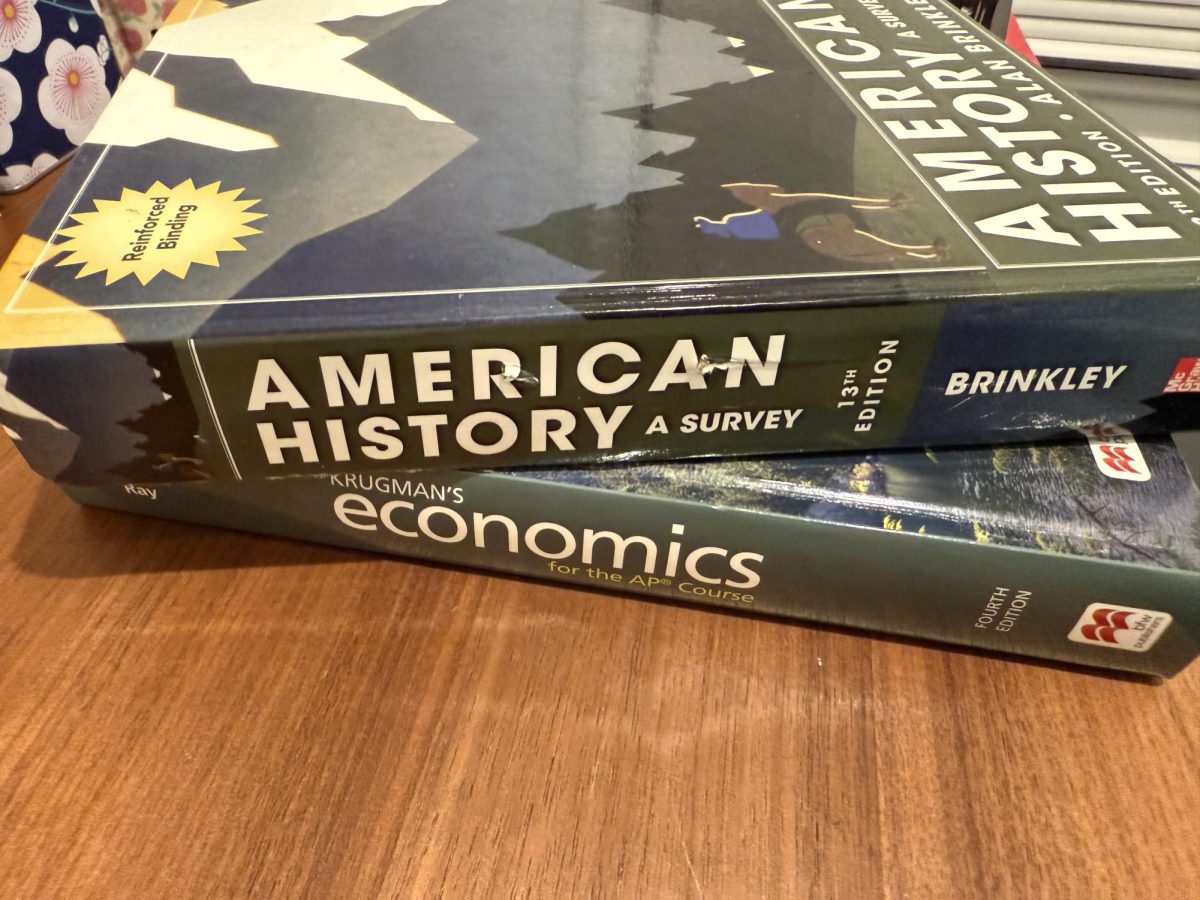

Despite this, it is prudent to understand that an issue can arise when this is the only type of literature teenagers are exposed to. When students are using sparknotes to summarize profound pieces of literature that have shaped modern understandings of text, but can devour a three hundred page Wattpad-esque novel in one sitting, they are failing themselves intellectually.

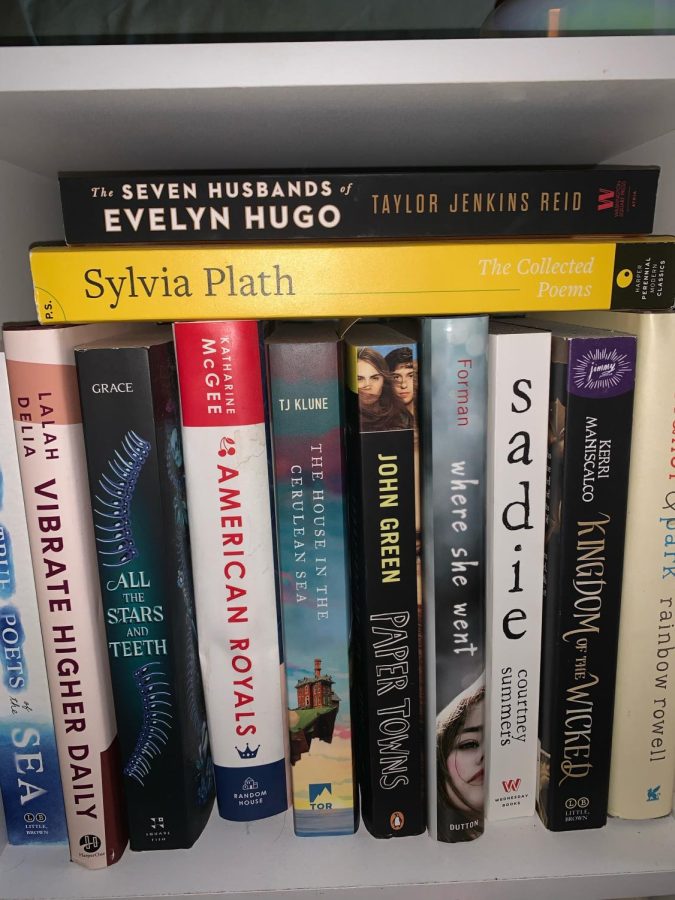

It’s far from all bad, however, popular authors such as Madeline Miller and Taylor Jenkins Reid come to mind as standout authors whose novels are never deprived of their soul simply for profit. But reading is so personal, so subjective, who am I to tell you what’s “good” and what’s “bad”?

Most importantly, “booktok” has undoubtedly promoted an incredibly healthy hobby and helped reintroduce reading as “cool” once again. So really, does it matter if someone chooses to use Hoover’s ever-popular It Ends With Us as an accessory if the hype around it got them to pick up a novel for the first time in years? No, probably not. But that doesn’t negate the idea that there should be a healthy balance struck between these “just for fun” reads and more challenging material.